This is the second post in a series on the creation of Divination’s setting and magical universe as defined by the tarot. The first post in the series is Making a tarot-defined setting, and you can find the entire series linked at the bottom of each entry.

The world of Divination is one wherein Pamela “Pixie” Colman Smith (a real life person who is lovingly fictionalized in our setting) depicted the Esoteric almost perfectly in her 1909 tarot deck. So perfectly, in fact, that the Art began to flow more freely into the Apparent, opening Third Eyes and creating Artists as it went.

When contemplating how to tell that story, and how to tell the story of the hundred-twenty-something years between the creation of the RWS deck and today, I spent a lot of time thinking about stories of magic and, always, the cards.

I knew using tarot for TTRPG would include breaking apart the deck—perhaps using some cards for their numbers, some for suits, and some purely for their meanings.

I came in knowing that I wanted eight playable Aspects, and which ones I wanted: the major arcana cards that stood in for human archetypes. So those were set.

After that, Nyx and I built the mechanics for Divination using the Lesser Deck (the aces through tens), which gave us our d20 on which to pin a fair game. That left us with the Figures Deck (the court cards), which felt tied to NPCs and their motivations, and the Greater Deck, all the big juicy cards that weren’t being used as Aspects.

For ages, I felt that Divination was setting-agnostic, the way the RWS framework can be setting-agnostic. You can pick up Tarot for Iguanas and you’ll know what you’ll get. That would let you tell an iguana-centric Divination story, and I loved that idea.

Nyx was the one to tell me that the world we were creating deserved a setting. And not just any setting, a tarot setting. I found that world in the fourteen cards we simply hadn’t started using yet.

Of course, I’d thought of those cards connected to RPGs before. Death, Lovers, the Tower—they’re so dramatic, they’re easy to use in stories as prompts, as random draws, as inspiration for worlds of magic. We just hadn’t used them here.

The idea lit a fire in me. I separated them and paired them. (If I’m being honest, I paired them and re-paired them and re-paired them.) I looked at lots of pairings before I could tell the story of these seven pairs well and cohesively, covering all the tarot-related ground I could from my years as a GM and storyteller.

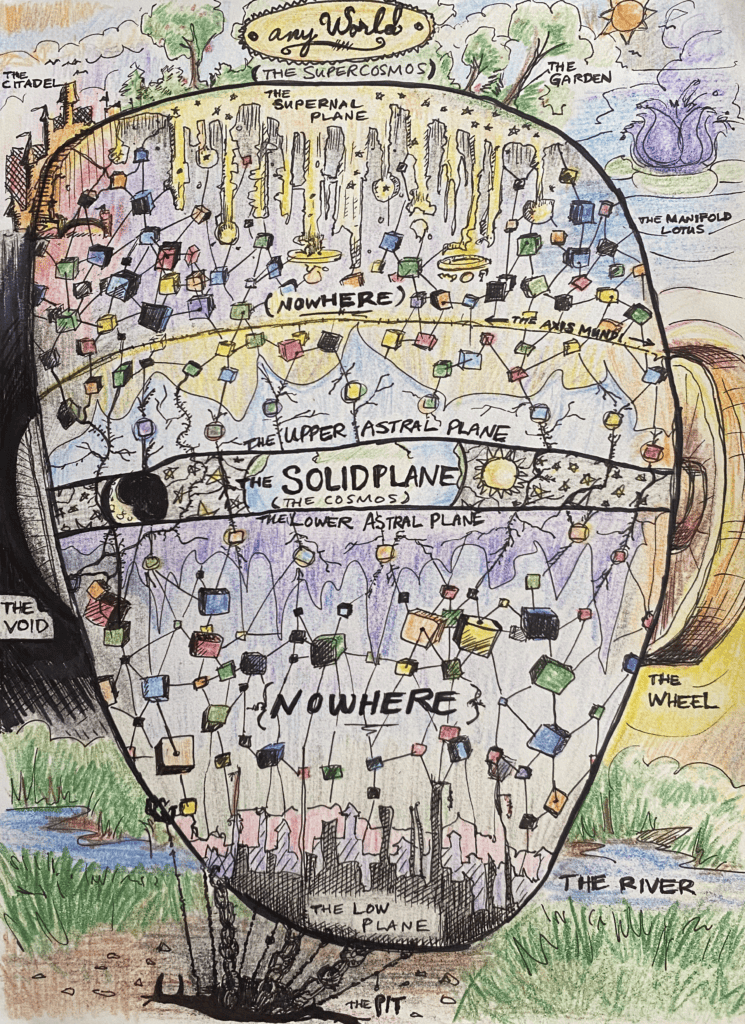

I took photos on my phone and made spreads to explain Esoteric reality, and even drew some trippy artwork, all as an effort of making a cohesive and deep world, all made of tarot shapes and concepts.

Finally, I landed on some pillars.

There were fourteen cards left after taking the Aspects out of the major arcana. Seven of these would represent Roads—paths, urges, drives, philosophies, prompts, and methods. The other seven would represent Sources—ways Artists are able to change reality with the Art.

Those terms—Art and Artist—represent my effort to distill what makes tarot special: the fact that its profound philosophies, lessons, and concepts are always a story told in illustration. Reading tarot is reading literal artwork.

What if, in Divination’s world, all of tarot’s philosophies were true? Or truer anyway. What if they were heightened, deeper, and more mystical, what would that world be like? What if those philosophies and lessons and hard ideas pointed at ways to do the impossible, as the occult world attached to tarot suggests? What would those Artists be like in culture, style, and manner? What ways would they form trust? When would they stick together, and when would they split?

I paired these cards, and sought these Roads and Sources thinking about the stories they might generate and the ways it might be fun to let players fool around with reality. I wanted people to make stories in a world with secret magic, brimming over and bursting into reality, the result of a great democratization in a post-Pixie-deck world. I wanted Artists who lived oddly long lives, and left blessings on babies, and knew how to call up a spirit to talk to, or how to anoint a home so no spirit could get in.

I wanted a world where the weirdest Artists could do weirder things, but that they mostly wouldn’t—because getting what you want always has a cost, just as every card in tarot has an inversion with all its lessons of transformation, balance, and fairness.

But most importantly, I chose the Roads and Sources to explore, examine, and play with the concepts of the major arcana cards associated with them. My hope is, when you come to understand details like why the Unwritten Road (The Wheel of Fortune) doesn’t speak to its Artists but The Road of Two Lands (The Chariot) does, it deepens your connection to those two cards. If you have a feeling of revelation when you understand the oddly parallel relationship between the Garden Road (The Lovers) and the Crooked Road (The Devil), or if you feel yourself moved by the things your story on the Shivering Road (Death) teaches you, well, that’s just tarot.

In my next post in this series, I’ll talk about the Road of Two Lands, the Source of Temperance it leads to, and its associated Artistic talent of Transmutation. Artists on The Road of Two Lands are the most like classic magicians—Artists whose Road urges them to acquire skill, attempt hard work, and cultivate ambition. A Hero on that Road would be challenged to gain power, but to learn to use it safely, and to avoid the hubris that might come along with its repeated use.

>> Read the next post in this series: This game will teach you tarot

Find the rest of the series here:

- Entry 1: Making a tarot-defined setting

- Entry 2: The Roads and Sources (this post)

- Entry 3: This game will teach you tarot

- Entry 4: The Road of Two Lands

- Entry 5: The Unwritten Road

- Entry 6: The Shivering Road

- Entry 7: The Crooked Road

- Entry 8: The Garden Road

- Entry 9: The Road of Scale and Blade

- Entry 10: The Road of the Infinite Loop

- Entry 11: Itinerant Artists

- Entry 12: The Esoteric Renaissance